The field of medicine has made admirable strides in gender equality. In 1981, just 13% of physicians in Canada were women. Today, that number is 44%1 and growing.

In celebration of women in medicine and #IWD2023, we sat down with Dr. Nadia Alam—family physician, anesthetist, past OMA president, health policy analyst and mom of four.

Read on to learn more about Dr. Alam’s experiences as a physician, her perspectives on physician burnout and her advice to the next generation of women considering a career in medicine.

What inspired you to pursue a career in medicine?

I decided I wanted to be a doctor at a very early age—it’s funny because I didn’t even know what it meant to be a doctor at the time.

When I was just starting school, my dad was visiting with a work colleague in our living room. I walked in and my dad put his hand on my head and introduced me. In response, his friend simply said, “Oh, she’s a girl. I guess she’ll never be a doctor.” And you know what my dad said? “Why not?” And that stayed with me. “Why not?” I thought. “I am going to be a doctor.”

Luckily, I happen to love medicine. Stubborn childhood determination may have been the catalyst, but my passion for the work and the people I care for have sustained me.

Why family medicine and anesthesiology?

I started out believing I would pursue cardiology because my dad has heart disease. However, I ended up falling in love with family medicine, and soon after, anesthesiology too. Though it doesn’t seem so on the surface, the two have a lot in common, which is why I think I was drawn to them. For both specialties, a physician must know so much about so many things—about the body, about a range of illnesses, and about patient values. They each constantly present new challenges so my work never feels repetitive. The difference between the two is in the timeline. In family practice, I typically have years with patients, while in anesthesia, I have minutes.

What challenges and opportunities in medicine do you feel are unique to women?

Despite women being increasingly represented in medicine, what still surprises me is that sometimes I’m treated differently—entirely because of how I look. And this different treatment can come from anywhere: from colleagues, allied health providers, patients or policy makers. I work in an empathetic field devoted to compassionate, unbiased care and yet a gender bias still exists, even in that environment. There are opportunities I haven’t received, but that I’ve seen male doctors receive, despite being as well-spoken or perhaps even more qualified. I’ve had patients seek out a second opinion from male physicians. I’ve been questioned about my training and expertise as well as ‘where I’m from,’ yet I have male colleagues who’ve shared that they’ve never been asked those questions.

On the flip side, I wouldn’t trade my experience for any opportunity. Patients tend to give me their trust quickly, and as a result, many are open to sharing not just their physical concerns, but their psychological and social concerns as well. This helps me see and understand the whole person quickly so I can provide even better care. Of course, male doctors foster great relationships too, but in many cases trust might take longer to develop.

As not just a doctor, but a wife and mom of four, how do you balance your work and personal priorities?

I don’t! I have a checklist that I do my best to get through every day and week, but the checklist never ends. I’m fortunate to have a husband who is equally involved in parenting and that helps share the workload.

Cutting back my work hours to around 50 per week has made a big difference. I am better at balancing the demands of my job and the needs of my patients without sacrificing precious moments with my children and family. Still, I accept that I will always feel stretched. Balance for me is celebrating the victories when they happen, enjoying the moments I can, and knowing that perfection is not the goal.

You have spoken publicly about your experience with burnout. Can you share more about how it showed up for you and how you addressed it?

I burned out two years ago.

Like many of my peers, I was working as many as 80 hours per week during the pandemic dealing with very sick patients. I was undertaking risky procedures—and by risky, I mean I was risking my own health every day to get the job done. By extension, I was risking my family’s health when I returned home each day. I worked hard to provide information on the pandemic—not just to my own patients, but to the public—and was involved with creating policy around primary care and the pandemic. Apart from that, I was dealing with a number of challenges within my family.

Physicians strived to be a calm voice and a steady hand in the storm, but the pandemic took an immeasurable toll on many of us.

I talk about burnout openly because physicians are conditioned to have a stiff upper lip. We don’t give ourselves the space to be human. We don't eat or sleep at normal times. We don’t always make it home in time to see our own families. On top of it, the work we do can expose us to brutal moments in a person’s life, and those heartbreaking moments leave lasting scars. Trying to work in a system that’s broken adds moral injury on top of it because we know our patients and their families deserve better.

I realized that things had come to a head when I felt like I was just suffocating at work. So I took a leave of absence to weigh whether or not I could continue working in medicine at all. It was one of the hardest choices I had ever made—to choose myself. Sometimes I think burnout was a blessing in disguise, because it forced me to wake up and really look at how I live my life. Since then, I have actively worked to change. I spend more time with the kids doing simple mom things like picking them up from the bus stop or helping them with homework, as well as special things like taking them to paint pottery or go bowling. I take time for my own hobbies, something I haven’t done in well over a decade—painting, cooking, exercising, and sleeping more.

Addressing burnout requires effort at the system-wide level. It requires politicians, policy makers, administrators and other stakeholders to innovate and create change. My role in this is to stop sacrificing my health and sanity to prop up a system that isn’t fair or just or equitable. For years, I skipped taking care of myself so that I could take care of others. Now, I have changed my perspective to prioritize things according to what must be done versus what could be done versus what would be great to do but just isn’t critical or important to me. Instead, I work hard to fill most of my day with what I value, the people I love and actions that are meaningful. And some of that is medicine.

I’m not out of the woods. Most days, I’m still somewhat burned out. But I am better, and that means a lot to me.

What are the most rewarding parts of the job for you?

My job isn’t just intellectually challenging, it’s emotionally fulfilling. I get to watch people as they move through their lives. I get to be there for their most vulnerable moments, but also their most extraordinary moments. I am constantly bearing witness to lives well-lived, and that’s beautiful. To know that I can have a direct hand in helping people—in changing the course of someone’s life for the better—is unbelievably rewarding.

What advice would you give to young women considering or just entering the field of medicine in Canada today?

Be prepared. You’re getting into an incredibly demanding—but incredibly rewarding—field. Don’t forget to take care of yourself. You may feel the need to work harder to prove yourself as a physician or as a partner or mother. You may wonder if you’re really seeing, or merely imagining, a bias at work or in society. You’re not, unfortunately. But you’re also part of the transformation. The face of medicine is changing. The face of medicine looks like me. It looks like you. Whether you’re a woman or Black or Indigenous or non-binary, medicine now looks like you. Whether you come from privilege or are a refugee or have a different accent, it looks like you. And you’re exactly what’s needed to create a well-rounded system that is truly representative of—and responsive to—the patients we care for.

About Dr. Nadia Alam

Dr. Nadia Alam is a “scrappy small-town family doctor and anesthetist” with nearly 15 years of experience in both specialties. She teaches clinical medicine to medical students and residents through the University of Toronto Department of Community and Family Medicine, as well as a masters-level course, Fundamentals of Health Economics and Policy, at the Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation. She actively advocates and sets policy for the healthcare system on a local, regional and provincial level. A Board Director at the Ontario Medical Association from 2017-2020, she also held the role of OMA President. She has received multiple accolades, including:

- 2022 Eugenie Stuart Award - Teaching

- 2020 Canadian Women in Medicine Inspiring Physician Leader award

- 2020 Louise Lemieux-Charles Health System Leadership Award

- 2018 one of Toronto Life’s Top 50 Most Influential People

About Women at Dr.Bill

Dr.Bill is committed to championing gender diversity. As of March 2023, 60% of our workforce are women. Not only is our CEO a woman, 52% of our leadership positions are held by women too. #EmbraceEquity

About International Women's Day

International Women's Day (March 8) is a global day celebrating the social, economic, cultural, and political achievements of women. The day also marks a call to action for accelerating women's equality.

IWD has occurred for well over a century, with the first IWD gathering in 1911 supported by over a million people. Today, IWD belongs to all groups collectively everywhere. IWD is not country, group or organization specific.

The aim of the IWD 2023 #EmbraceEquity campaign theme is to get the world talking about Why equal opportunities aren't enough. People start from different places, so true inclusion and belonging require equitable action. Read more about this here.

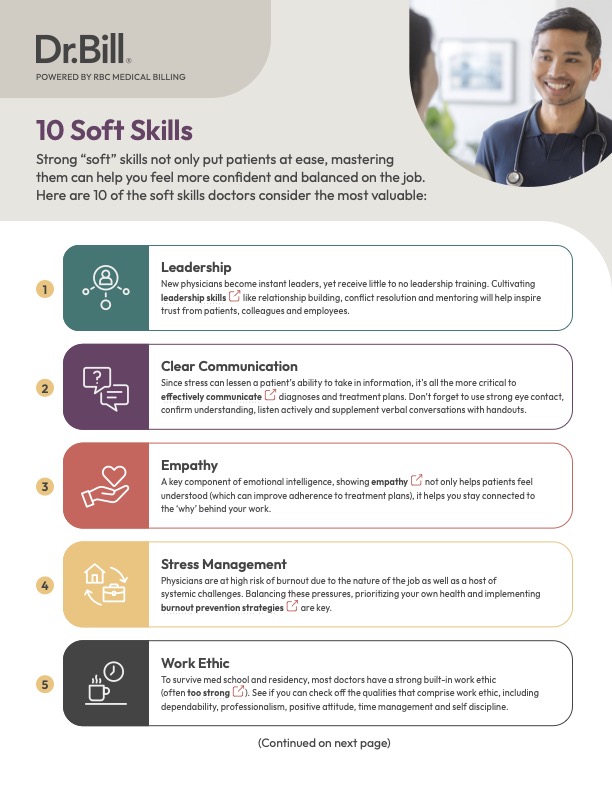

10 Soft Skills Every Physician Needs

Soft skills for doctors are an essential part of the job. Unlike almost every other career, at the core of the medical profession is someone’s well being.

Download the checklist to learn the 10 soft skills every physician needs.